Contents

- Two questions

- What is our motive for looking for risks?

- The power of incentives

- How can we master and control our risk motivation?

- How do we compensate for perceived risks?

- What distinguishes RMT from RHT?

- Can we describe risk-taking behavior holistically?

- Implications of Risk Motivation for the “Real Life”

- Implications for reducing accidents

- The insurmountable desire for challenges in our daily lives

- A personal conclusion from the author

Two questions

The topic – how the psychology of risk-taking behavior works – is split into questions.

- Research implications of a motivation for risks

- Is there a Personality Factor when taking risks?

The sample of people does not exist out of professional risk takers (soldiers, fire brigade, police, civil protection, stuntmen, race car drivers, …) but mainly of young white men and university students from a medium-sized Canadian city.

Evidence for a general risk-taking personality trait, statistically significant, was not as strong as some theories predicted. This may be due to the sample, but most theories had comparable samples, resulting in doubt that the level of influence that personality traits may have on risk taking.

The conclusion is that risk factors of personality traits play an important role in the risk-taking behavior, but that their role is less important than that of situational factors. The results have important implications for risk-taking research and for safety measures (eg Task-specific selection and risk training).

What is our motive for looking for risks?

Most theories of expected utility considered no emotional, nor physiological components, of the positive aspects of risk taking, nor the importance of non-materialistic rewards. The RHT (Risk Homeostasis Theory) also does not regard risk (taking) as something one can desire or a pleasant undertaking, but as a purely extrinsically motivated activity with risk tolerance. However, people look for intrinsic as well as extrinsic rewards. E.g. therefore also pleasant emotions and pleasant excitement. The literature on emotion, motivation and the interpretation of such studies suggest that these factors are more effective for adressing of motivations for risky or safe behavior than important rewards, which (the latter: rewards) one obtains with more focused behavior.

The tests also postulated that the subjects generally test their limits, try their luck and risk their chances by taking risks. Nobody took a completely safe course, everyone followed some too risky reactions. This explains the intrinsic need, desire and motivation of the subjects to take risks. However, the differences between where, how and how much risk they want are large.

The conclusion is that people feel intrinsic reward for taking risks, such as hormonal pleasure experiences, stimulation of a physiological pleasure center, emotional pleasure, the experience of small differences between the desired – and the target level of risk, of the unity of action-oriented – and targeted risk-taking behavior. We therefore take risks for both the intrinsic pleasure and the extrinsically favorable benefits.

The power of incentives

Risk motivation theory (RMT) and Risk Homeostasis Theory (RHT) both state that incentives for safe behavior are a powerful motive for reducing risk-taking trends. Changes in the risk content of a situation will lead to a higher involved control and therefore to compensation behavior. Externally introduced safety benefits are virtually canceled out. External incentives for safety also manipulate the intrinsic motivation of subjects by changing the desired target level of a risk. The target level of a risk is influenced by a higher advantage of safe behavior and higher cost of risky behavior, so the subject chooses a less risky strategy.

An additional finding is that target levels are constantly adjusted according to the perception of the risk level of the subjects.

This suggests that incentives should be used for safer behavior. Social rewards are stronger than financial ones. Social incentives are more likely to trigger intrinsic motivation. The data also suggests that incentives work better than punishments to stimulate safe behavior. So “Fame” works stronger than “Fortune” or “Pain”.

This also applies to phobias: people with a phobia keep their behavior until an alternative behavior is realized that is more rewarding than the avoidance behavior with regard to feelings such as fear.

Whether incentives work most effectively on a physical, economic or social level, or if being presented as conditional for good performance or rather as opportunities in a lottery, can depend on the individual, the situation, or the culture and is worth further investigation.

How can we master and control our risk motivation?

People strive for increasing control and we adjust our behavior according to the situation / needs, even when the perception of that control is an illusion. When a situation or an illusion of a situation with more uncertainty and unfamiliarity presents itself, we become more careful, until a less risky situation presents itself.

In gambling, such as throwing a die with a 50% chance of the outcome of three or less versus a result of four or more, many engaged in some form of superstitious behavior, such as throwing harder for higher numbers, or e.g. systematically gambling for low numbers after a few times high numbers. Or assigning their success to the previous course of the day, their happiness in love, the moment of the day, etc.

Most people do not realistically perceive their own situation, but have a positively colored illusion about themselves, their skills, and their ability to control the environment. Such findings confirm the importance of involving individual perceptions of personal control, even illusory, when analyzing risk-taking behavior. They show that the perception of control, or lack of control, leads to corresponding risky or safe behavior. “Don’t worry, I’ve got it all under control” is a famous final phrase just before an accident. Giving the feeling of control with seat belts, ABS, four-wheel drive and helmets, etc., therefore leads people to riskier, ill-considered, or even careless behavior.

How do we compensate for perceived risks?

An important underlying assumption of Risk Homeostasis Theory (RHT) and Risk Motivation Theory (RMT) is the behavioral compensation for observed changes in risk content. People show compensation behavior to reduce a difference between their perceived and desired risk levels. The risk-taking strategy variable DFO (Deviation from Optimal Response Pattern) also showed these behavioral shifts as a result of changes in the probability of punishment. This was predicted by the RMT, which states that each change results in a new perception and the target level of risk reset.

What distinguishes RMT from RHT?

RMT is based on RHT with its compensation behavior feedback loop for the perceived difference between desired level and target level of risk. RHT, on the other hand, does not consider the frequent, continuously shifting target levels of risk nor the risk-seeking tendency of people.

RMT is an extension of RHT, stating that physiological and emotional processes undergo the same compensation functions as the rational cognitive processes on which RHT primarily focuses.

RMT states that people take risks for intrinsic rewards associated with performing risky activities and that this process also has a compensation feedback loop.

All in all, the RMT extends the RHT with the following:

- a) Postulating multi-target levels of risk that require constant compensation and may never achieve a homeostatic controlled risk optimum.

- b) The strong emphasis on individual motivation processes, rather than collective behavior of a larger population.

- c) The importance of emotional and physiological aspects in assessing and evaluating risk-taking behavior.

- d) The addition of action-oriented rewards (desire for risk) to the goal-oriented rewards (risk tolerance).

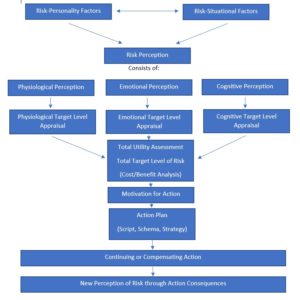

Can we describe risk-taking behavior holistically?

The difference between the RMT and other theories is that it combines many facets of risk-taking in a single holistic model. It takes into account the desire to take risks, as well as the desire to control it. It involves processes that do not occur consciously, such as physiological and basic emotional processes. RMT emphasizes the emotional, physiological, and cognitive aspects of risk-taking and a behavioral compensation feedback loop, designed and developed to optimize the overarching benefits of risk-taking.

The components of the ‘Risk Motivation Theory’ (RMT)

Implications of Risk Motivation for the “Real Life”

Although it seems obvious that people are more cautious when there is great danger, this theory also implies that people voluntarily increase their exposure to danger when the perceived risk is low. This has implications for industry, traffic, health issues, and personal life. The findings teach us that if we make the environment safer, people will compensate for this increased safety by taking more risks.

Implications for reducing accidents

This is important for the design of the workplace to reduce accidents. The less active input an employee has when working with machines, the higher the chance of boredom, too little excitement, and therefore, compensation for risky behavior. E.g. duels with oil barrels, or races with fork lifts.

That is why it seems important to involve the employees in the design and execution of their job. The amount of responsibility that one experiences is probably proportional to the amount of risk that one experiences. Risk-seeking behavior must therefore be considered if accidents are to be avoided.

Encouraging safe behavior through reward programs may lead to habituation and increased risk-taking over time. To address this, we should periodically change rewards, tailor them to individual needs, and use non-material incentives alongside material ones. Praise and fame often affect intrinsic motivation more than material rewards.

The government should actively implement and enforce security measures within family settings for maximum effectiveness. Learning from childhood safe behavior and rewarding children for displaying risk-conscious behavior could be much more effective than changing adult behavior. The same is true for forming an employee’s desired behavior from the start of employment.

Recognizing danger is crucial in risk-taking. If a risk is not perceived as a threat, it cannot be appropriately addressed. Therefore, individuals must learn and train to recognize danger to prevent accidents. For example, consider the difference in the handbrake-wheel combination between a bicycle and a motorcycle. On a bicycle, the right hand brake controls the rear wheel, while on a motorcycle it controls the front wheel. Not being aware of this difference can lead to accidents.

The insurmountable desire for challenges in our daily lives

However, one must also realize that regardless of the reward or punishment, most people still take risks. After all, taking risks is important for survival, and is intrinsically and socially rewarded. Instead of eliminating all risks, one should therefore channel into equally risky actions for the individual, but which are less risky for society. E.g. taking risks with a race car are more tolerated than taking the same risks with a truck with toxic waste.

We must, therefore, try to let people actively choose which risks they take, limit the situations in which they take them, and look for other situations or locations where and when they want to take risks. People must also learn to estimate the costs and benefits of this action.

The anticipation of having fun and the actual experience of emotions and physiological arousal are very intense under risky circumstances. The increased pleasure provides a powerful incentive to sort out situations that can give us that feeling back.

Individuals and situational factors influence the level of pleasure experienced from risk-taking. Testimonials suggest that higher perceived risk increases excitement and motivates individuals to exert more effort in controlling the hazard. For example, the measures taken to protect public figures on a race track correspond to the level of danger involved.

The effects of the illusion of control have potentially important implications. Most of us have the illusion of control, optimism, and skills. We may all be at risk to the level we feel comfortable with. As we overestimate this level, we may all take too high risks. This has consequences for our survival as a species. Namely, if no other factor compensates for this phenomenon, we should have died out already, or this will happen soon.

A personal conclusion from the author

Given people’s insatiable motivation to do more, he hopes that our drive for more risks will be accompanied by a proportionately strong drive to master and control risks and the environment so that one does not have to take the ultimate risk just to know what happens in the hereafter. Perhaps the consequences of taking that risk would ignore the optimum level of the challenge.