Future-Proofing The State by editors Jonathan Boston, John Wanna, Vic Lipski and Justin Pritchard

Future-Proofing The State comes out of the aftermath of a number of short-term major disasters in Oceania. Disasters were flooding, bush fires and a huge range of earthquakes in a short time. It is a vision of what they need politically and in terms of public service. The book has four parts, all four related to resilience, risk management, crisis management and disaster recovery. I attempt to summarize the main thoughts below.

Part 1: Governing for the Future

From the mission of running a government there are some priorities that one must ask. Among many others are:

- Arrange the finances in a responsible manner

- Where to save but also where investing is the key question.

- Building an increasingly competitive economy, adapted to its time.

- The provision of better public services within ever more pressing conditions, which increasingly require the relevant services of the civil service to do with limited resources, affordable for taxpayers.

- Caring for future generations, a call that is becoming increasingly necessary.

In addition, the government increasingly needs good advice, as well as capable people who find it a challenge to and must know that their decisions have an impact on the economy and society, and the associated opportunities and threats, now and in the future.

The complexity and the scale of the risks (= threats and opportunities) of society become ever greater. (Eg due to climate changes, terror, cybercrime, dependence on all kinds of infrastructures that are still vulnerable, such as electricity, water supply, …)

The frequency of major disasters on a global scale is also increasing. At present, the global arrangement of common resources, such as oceans and atmosphere, is still in its infancy and weakly regulated. It increases the likelihood of the required political will at world level coming too late, unless supported by the citizens or enforced bottom-up. That will weigh heavily on the recovery that future generations will have to carry out.

Therefore, the current government should not fall into the trap of short-term vision under the pressure of elections, but they (the political parties) should work together, and not choose against future generations in favor of short-term vision within a reign cycle.

Governments need a resilient society to be resilient themselves. A continuous future-oriented view therefore becomes increasingly necessary as well as taking care of the scarce social social capital.

It is therefore important that the leaders of the government, the ministers and their cabinets, know all sides of the decisions to take, have all relevant information at their disposal and know the foreseeable implications.

Although the government is not currently a technocratic exercise, it is the task of the government, through difficult issues, to make the right and most sensible decisions, depending on what comes to society. In this way, society can progress sustainably. Trust between citizens – politics and civil service is essential in this.

Increasingly looking ahead is therefore essential, also to create and maintain trust.

The civil service and politics must therefore, hand in hand, focus on determining which services are most effective and most cost efficient. Because the public expects the government to have a well-oiled machine that helps them when they need it. And they’re right.

We do not want targets that are easy to achieve. The execution of the services may be difficult to achieve and feel uncomfortable. In doing so, we do not shy away from difficult issues.

But the first lesson to draw is that the authorities must have a foresight strategy or a foresight team. This way, they can ensure that people take the future into account to a certain extent. This is in stark contrast to the political planning, which typically has the duration of a political cycle.

Important aspects that increasingly need to take into account are the change in the climate and the far-reaching concentrations of population and goods. Both lead to an increase in disaster vulnerability, such as pandemic, financial crises, cybercrime, solar storms and social unrest. In addition, global disasters can occur instead of the smaller “major disasters”. One of the generic methods to challenge this is diversity. In everything. Determine priorities in advance. In doing so, you must give attention to the storage of necessary stocks. In private, one must pay more attention to sharing data. The sectors must learn to abandon their preoccupation of keeping things confidential.

In order to be able to do resilience in this way, one must realize that this is something one realizes slowly over a longer period. In order to build a resilient society, we have to make work of the individual and of the communities. It takes a certain sense of civic responsibility to work together, to achieve better results at a lower cost. A country that realizes this is not only better positioned in predictable circumstances, but also in unpredictable chaotic circumstances. When creating solutions, the institutions of the government must also contribute. There is also a danger that governments that are most successful with a previous concept of governance will find it more difficult than governments that create and implement a different model of governance. In order to frame an adaptive system of governance, one requires four ways of thinking: compliance, performance, emergence and resilience.

It is important that the government does not do everything alone. It must exchange knowledge and skills with the private sectors. Co-creation and co-production are important means of binding in society, between the government and the citizen and the private sector. But also self-organization and self-confidence are important for the citizen. New techniques play a role in this. It may create more possibilities and it will be more cost-effective to make use of it than the start of a new political program and legislation to change behavior.

But to know what the government can do, it is important to know more about how society connects to itself. I refer to an earlier article in which I talk about linear, complicated and complex problems: “Does history repeat itself? Or not?”. I repeat here the explanation:

What are linear events? These are generally events that one adresses by applying routine tasks. For example, chopping a tree with an ax. You must think about where the tree can best fall down, because it does not always fall correctly, but in general this is a task that requires no special higher studies. Which does not mean that no responsibility hides behind such a task.

Another thing are the complicated things. These are things that, with sufficient effort, such as acquiring sufficient knowledge, are just manageable and predictable, but not for a layman. For example, building an airplane. You have to know enough about aerodynamics, materials, fuels, strengths of materials, standards, fluid dynamics and nowadays even electronics and computer sciences to design an airplane. But we succeed, provided we work together.

Third, there are the complex phenomena. These are things that we absolutely can not predict. Not so much because we can not know our own actions, but mainly because we can not know all the parameters, among other things because they are never the same twice. Some examples are nature, climate changes, society, …

In addition, the term “wicked problems” exists. These are problems that have no immediate or clear solution. They are often related to “unknown unknowns”.

In order to be able to cope with these situations, the government must get all interested parties in line with their perspectives and goals. But that requires a sharpening of patience, and consensus building. This means that one cannot avoid complex matters again.

A case with which the government can deal with resilience is building scenarios. That is a linear approach to uncertainties. Non-linear approaches are also required, such as back-casting, policy gaming, and horizon scanning.

In doing so, it must always take into account that no form of looking ahead is 100% congruent with the volatility and uncertainty that exists in an increasingly complex world. But it remains necessary to become proficient because they are strategic risks.

This gives reason to reason that governments have to be careful with the implementation of lean systems. Lean systems that only focus on efficiency are very likely to have insufficient resources to avert unexpected disasters and also to make plans for a complex world full of ‘wicked problems’.

The next question is whether the government has the problem of political myopia. This question came about due to the large global financial crisis (around 2008) and gave the impression that this was due to a lack of forward looking and only linked to the public sector. However, both are a misconception.

In Future-Proofing The State‘s Chapter 7 describes a new issue: every failure of a regulation is a new challenge: what went wrong? Why did it happen and how can we ensure that this does not happen again? How can we learn from our mistakes? (These questions do not only apply in the public sector, of course.) In this respect, take in mind that regulatory regimes often fail when they make promises, which create great expectations, but when they do not realize them, and the parliament then decides to develop a new regulation. Sources of non-compliance are often the failure of the business of the too complex regulations, but also a lack of commitment of the business to the underlying thoughts of the legislation, or the business finds the regulations unjustified, or the implementation is too expensive. …

Is it possible, however, to maintain the trust of the citizen and private sector in the government? After all, trust, integrity and social norms are very important for the future-proofing of the state. To be able to say something about this, one uses the international Corruption Perception Index (CPI) scores. The importance of this is that a society with higher confidence in the government will achieve better social, democratic and economic progress. A point to interprete here is that this index revolves around perception, not the factuality. Openness and transparency are extremely important, as well as self-criticism.

Part 2: Managing Risks and Building Resilience

A first question that arises when the government starts such a task is: what can we learn from the private sector? An important approach is that new risks characterize modern companies. You can associate them with a growing state of science and technology. They are global in nature, and cross national and organizational boundaries. These are side-effects of innovations, that expose the public, private and government to risks. They are “man-made”. On the other hand, there are the “natural hazards”. There expectations of anticipation and control are unusual. One conclusion is that the government must ’empower’ multiple stakeholders in the regulatory process, at national, regional and local level. If this happens, the future-proofing of the state will be a co-operative realization, with an emphasis on ‘governance’ rather than ‘government’.

From chapter 10 in Future-Proofing The State, the actual sources of the text becomes more important: the disasters that hit the areas in Oceania in 2009-2012.

In addition, there is the important conclusion from which one can assume that one must better equip the communities to survive and recover from disasters. Self-reliance is a key concept here. One of the important mistakes that a government can make is that it does too much for the citizen, because they will start to expect more and thus take fewer initiatives. This gave rise to a large number of victims in the past.

Another key interest is the alignment of the services that have to do their work in a disaster, and that they know each other what they have and can expect from each other. It is also important that the citizen knows that a literal immediate help is not always possible, and that (in Oceania) the citizen on his or her own behalf has to be able to endure it for three days on its own. Queensland even posted on its website: “Weather events are getting more severe and when a major weather event hits you. You need to harden up by preparation, awareness and helping others. “

A next chapter in Future-Proofing The State, chapter 11, deals with the reduction of future vulnerabilities in socio-economic systems. The author deals with this in a qualitative way with the understanding of hysteresis loops from the exact sciences. These types of phenomena often occur in complex adaptive systems. It is important to know that a change in circumstances can be irreversible.

In chapter 12 the author deals with the importance of horizon scanning as a technique that is important for exploring challenges and opportunities at policy level. It deals with questions such as: how do we identify relevant issues and trends? How do we graphically represent them? How do we make effective and flexible strategies from this information that prepare the decision makers for our coming changes? Analysis techniques such as “STEEP” are important in this respect: the search for changes in society, technology, economy, the environment and politics.

Chapter 13 is more practical: it concerns the influence that the delivery of a type of transport system can have on the future. In addition, the authors examine four hypothetical scenarios: “super city”, “coastal tree”, “carbon crunch” and “global bust”. They also looked at unconventional transport like flying cars. This involves a lot of questions such as “How do we translate this into action?” And “How can this work for the citizen?”.

In Future-Proofing The State, chapter 14 an important statement about resilience is that “no system is resilient when the economy is failing to improve the livelihoods of the majority of the people”.

Part 3: Managing Crises

When you think about crisis management, you are dealing with the “un-words” that dominate: unplanned, unwanted, uncertain, and unpleasant prospects and choices that you have to make. A crisis also works as a high-pressure cooker: they strengthen the interests and emotions to unprecedented high intensities. Questions one quickly asks are “How could this happen?”, “Why did not we see this coming?”, “Who is guilty?” And “How are we going to carry on now?”. But a crisis is not always a bad news show for the leaders. They can give unique opportunities to come up with old policies and old commitments, start new commitments and policies and reorganize the business.

Two logical types of actions occur for each crisis. First, there is the action in the plans that one makes. The second is the game of “who is wrong”, where the lawyers have months or years to decide where the crisis managers have seconds to make a decision under high pressure. So politically, a huge threat can come from a crisis.

But it can also bring huge opportunities. Politically, a leader in the crisis can be the hero, the victim or the criminal. The challenges for him are: first making sense of the crisis (making the diagnosis: what exactly is going on?). Second, making the right decisions. Thirdly, there is the optimal use of scarce available resources. Fourth, there is the giving of meaning: convincing the citizens and the media of their own insights of what is going on. Finally, there is the adjustment to the new situation: the citizens have to go on with their lives, continue after the crisis and look further at a new horizon, to reflect on the present, and to draw lessons. Renewal would therefore be a better word than recovery.

Take note that the crises are becoming more challenging: they occur more and more in cascade and cross borders and become larger. There are also more and more of them. But the means to avert, prevent or combat them are less and less available, owing to the fact that the authorities consciously want to work more lean. It is therefore necessary that one sees crisis management as an integral part and crucial dimension of leadership within and outside the government.

Another consideration, in chapter 16, is that all organizations have to deal with seemingly permanent changes.

First, there is the (attempted) debt reduction in the developed world, which exceeds a large number of generations. (“The blame has come naturally, it will disappear naturally also, of course!” is not true.)

A second consideration is that free information becomes an ever-increasing ‘force’. The government no longer has any exclusive rights or power over it.

Thirdly, there is the ongoing shift of wealth, power and influence from our traditional markets to the Asian-Pacific region and other emerging economies.

While parliamentary liability follows the course of the money, one should monitor the course of the world more closely.

While crises in the government in the past 20 years, especially meant not to be negative in the media, it means more and more managing the operational and financial risks in the coming decades for the huge expenses that we will face. A problem here is that the authorities still have to develop these skills.

Part 4: Disaster Recovery

This part immediately builds on the experience of disasters on a large scale. Restoration means governance that is much more than “fixing the dams” (which, for example, was necessary in New Orleans). A key behavior is to avoid putting the head in the sand, which inevitably leads to a new greater exposure to future disasters. Bridges must be built between civil, business and political leadership. However, this in itself is a “wicked problem” in which one will have to make non-obvious and non-trivial choices.

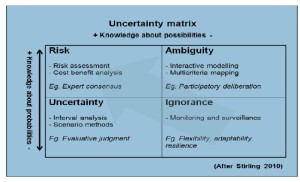

Perhaps the most important lesson learned is that one must confront governments and social vulnerabilities in society. Recovery is also something complex, where there is no such thing as a simple solution to problems, no quick wins, no return to normal. Recovery, in short, begins when the community restores or develops social, political and economic processes, as well as the necessary institutions and relationships that help it all work in the new context after the disaster. The term “recovery governance” is created here. This is most simply represented by the following table:

This shows that risk management is only part of the total problem. One cannot measure all problems of a disaster scenario.

In the event of disasters, one cannot resolve the problems simply as issues in a school exam, in which the teacher provides all necessary information. Possibilities for solutions are always with a large degree of uncertainty. It is therefore often not a solution to outsource the problem to a professional consultant. He often knows things less than the government. To solve these issues we must:

– firstly, focus on not only preparedness (readiness) and response, but we also need to work on reduction and recovery.

– Secondly, we must ignore the physical and economic dimensions of recovery, and deepen our understanding of the social, cultural and political dimensions.

– Thirdly, in addition to the obvious importance of the technical aspects and details, we must pay attention to ethical and moral dimensions.

– In addition, fourthly, there is the choice in the dilemma between speed of solution versus deeply thoughtful deliberation on the issue.

– Fifthly, there is the question of whether to tackle a crisis top-down or rather bottom-up.

– Sixth, there is the story of the ‘insiders’ versus the ‘outsiders’.

– Seventh, the fast-effect of the crisis creates a tension between openness and closeness, whereby a bureaucracy can opt for or oppose the proper spending of time and energy to learn from the current crisis.

– Eighth there is the contradiction between rights and obligations of the stakeholders.

– Ninth, there is the question to what extent “business as usual” continues to apply during and after the crisis.

– Tenth there is the obligation to work out and operationalize a cost-effective recovery that must meet self-esteem and practices that stimulate “learning-by-doing” and resilience.

Of course one needs debriefings after the disaster. What worked, what did not work, what could be better? The authors recommend a review by external experts. An important strategic lesson is to do work on more resilient communities, as well as on the individual, in order to better prepare both for the future. This is a shared responsibility between all stakeholders. The rule must be “Whatever it takes!”. That rule was not applied in the past, but was felt sharply after the 2009-2011 disasters in Oceania.

To do all this, the government is working on the “4 Rs”: “Reduction” of known risks, “Readiness” through capacity building, “Respond” to human need and “Recovery” after the disaster.

Response is important, because in the event of a crisis, unlike ‘business as usual’ everything can go fast. One can make decisions quickly, for example to prevent social insecurity and pessimism. In addition, future negative evolutions of disasters can be further prevented. It is very important that during the recovery phase, after the disaster, the pace of recovery is not jeopardized. At the same time, early intervention and keeping the current problem manageable are some important lessons from the major disasters of 2009-2011.

Chapter 21 talks about the innovations that are possible within the public sector, after major disasters. It shows four case studies of innovation in the public sector:

1 ° A secure centrally managed online system for sharing information about patients. This makes a lot of crucial time savings.

2 ° A joint venture between a number of organizations to support affected business with advice and guidance and benefits.

3 ° Adjustments in the functioning of the legal services, to ensure the continuity of their services, through a new approach with newer technologies that were available.

4 ° Support for affected families and households after the disasters, through cooperation between government departments and NGOs.

The central theme there was always: build up the services around the human needs, and not otherwise. Co-production between citizens and business and government for a better and cost-conscious approach to services was a strong factor that played a part in the aftermath. But co-location was also important: working from the place where one was, and helping with doing the work at that place by civil servants was an important factor in services at the front line. It was noteworthy that a lot of innovation occurred out of necessity. The intention must also be afterwards to turn this into innovation “by design”.

The book concludes with a chapter (22) on the role of an auditor general. Despite the rigor of that job, it appeared necessary, given the situation after 2009-2011, to be less demanding, for example in terms of evidence to be provided of correct expenditure and performance. This is